Oxeye Daisy credit Ian Phillips

Explore the Touchstones Trail

For those wishing to observe wildlife in the peace and quiet and discover the unique history of the site, the Touchstones Trail offers an opportunity to both enjoy the surroundings and learn more.

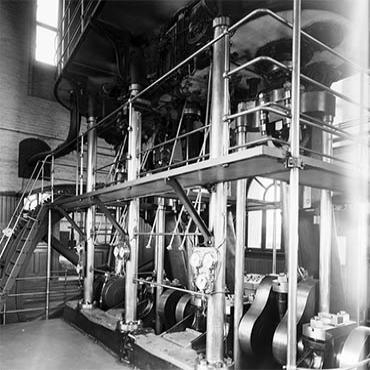

1 Triple Engine Room

At the centre of this room once stood a huge triple expansion engine. Fed by steam from the Boiler Room, the pressure drove three powerful cylinders to pump water from the Coppermill Stream into the reservoirs, and to the city.

Far from being a grimy industrial space, the Engine Room was always kept spotlessly clean and gleaming by the pumphouse workers. Steam power was eventually replaced by the diesel pumping engine, installed at the Engine House in the 1950s.

Although that engine has also long since disappeared, the pump it drove survived within the building after decommissioning in the 1980s, along with the fuel tanks and air starting cylinder. The pump had been electrified to match the others in the Turbine Room.

The pumphouse equipment that survived here at the Walthamstow Engine House was among the last of its generation in the UK, and is now very rare.

Tripe Engine Room

2 Then and now

For decades a chimney stack was a prominent industrial feature of the Engine House. It was demolished by 1960, after the pumping systems converted from coal to electricity.

The new 24-metre-tall Swift Tower now rises in its place. It includes 54 specially installed swift nest boxes.

The interior also provides a snug roost for bats.

Image from Thames Water Archive / London Museum of Water & Steam.

3 Reservoir Logs

The Metropolitan Water Board kept meticulous records of its employees, some of which have survived in archives. These offer us a glimpse into past lives and times working at the reservoirs.

Running the site smoothly required a number of staff just as it does today, but some of the jobs were very different. These included filterbed man, stoker, engine driver, boiler maker and boiler cleaner, dynamo attendant, engine cleaner and labourers, among others.

In 1905 engine drivers were the highest paid staff, earning £2.00 per week. The lowest earner was the poor old night-watchman, taking home just £1.45 and 6d for all those sleepless nights.

Geologists’ Association visiting Lockwood Reservoir excavation 1901

4 Heron Island

The big nests you can see in the treetops on the island here are part of the Wetlands’ famous heronry – one of the UK’s largest colonies.

There has been a heronry at Walthamstow Wetlands since the 1930s and it is one of the reasons we are now designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). Breeding herons peaked here in the 1990s with 138 nesting pairs; today there are around 40 active nests.

Herons begin nesting early in the year, before leaves are on the trees, so you may catch a glimpse of the chicks in March and April. Pairs often mate for life and may return to the same nest year after year, usually rearing 3–5 young.

Egrets and heron at Walthamstow Wetlands credit Ian Phillips

5 Songbird thicket

This habitat has been designed to provide cover for a variety of small birds, mammals, reptiles and invertebrates throughout the year. In spring and summer stop here to listen for warblers, thrushes, tits, dunnock and finches in song.

They are busy staking their territories, warning off rivals and attracting a mate. A few resident species such as robin and wren will continue to defend their territory even in the middle of winter.

Listen out for them even on the coldest days. In spring and autumn, passing visitors including warblers, chats and flycatchers may also be seen here during migration. They use the thicket to find food and shelter before continuing their epic journeys between Europe and Africa.

Songbird thicket credit Penny Dixie

6 The Roundhouse

This structure, called the Roundhouse, once sat in a formal Victorian garden and was topped with a rotunda built in a similar style to the Coppermill tower nearby.

This feature was demolished by the 1960s and all traces of the garden are long gone, but the valves housed below still act as an interchange between reservoirs 1 and 3 today.

The line of ornamental poplar trees you see nearby were also planted by the Victorians as an element of this garden – reflecting the contemporary attitude that this was a landscape that does man’s bidding.

Roundhouse at Walthamstow Wetlands credit Penny Dixie

7 The Grabber Crane

The automated gantry grabber crane clears 200 cubic metres of rubbish a year. That’s enough to fill over 2,000 baths.

It keeps the watercourse from becoming blocked by branches, bottles, cans and other rubbish that finds its way into the Coppermill Stream.

This area is also a good spot for seeing kingfishers, so keep an eye out for a flash of bright blue as these colourful birds fly along the stream.

Coppermill Tower and Grabber Crane credit Penny Dixie

8 The symbol of industry

The wooden wharf loading crane you can see here is a very rare relic of a bygone industrial age. In the mid-1800s copper ore was brought by sea from Wales and transported by barge up the River Lea.

Here on Coppermill Stream it reached its destination. It was unloaded using the crane before being worked into sheets and bars at the mill. Copper-rolling ceased production in 1857.

The mill was soon rebuilt by new owners, the East London Waterworks Company, who converted the site to a pumping station for Walthamstow’s first reservoirs.

The crane is now the last surviving evidence of that long-gone time – a ghost in the landscape. Visit the Coppermill Tower for more on the site’s amazing history.

Coppermill Crane credit Penny Dixie

9 Eyes on the skies

During your visit, don’t forget to look up. The open skies above the Wetlands are a rare sight in crowded London, and can be good for wildlife-watching, especially birds of prey.

Raptors are drawn to the Wetlands by an abundance of prey. Sparrowhawk and kestrel are regularly seen hunting overhead and the local peregrines also use nearby pylons as a convenient perch and plucking post.

During migration in spring and autumn other raptors may also pass through, including common buzzard, red kite, marsh harrier, hobby and, if you’re very lucky, osprey. On warm summer evenings at dusk bats emerge from their secret roost sites to feed on insects over the reservoirs. At least seven species have been found at the Wetlands to date, including the rare Nathusius’ pipistrelle – a small migratory bat from Europe.

Remember, it often pays to keep your eyes on the skies... and for a real birds-eye view of the Wetlands, visit the Coppermill Tower.

Birdwatching at Walthamstow Wetlands credit Penny Dixie

10 A unique view

Stop a while and experience a view with a difference. Urban, industrial and natural features meet here at the Wetlands to create a unique environment.

The busy railway connects London to East Anglia, with countless trains passing the wide expanse of the operational reservoirs. On the city skyline, you can see landmarks such as Canary Wharf, the Gherkin and the Shard. To the south-west, you can also see local landmark Springfield Park.

Yet despite these reminders of our urban environment, you may also begin to notice the peace of the Wetlands and the wildlife that thrives here. The water’s surface reflects the changing mood of the wide-open sky. The birds carry memories of other places far away, from Africa to the Arctic.

Watch the skies, watch the water, and enjoy the moments of solitude and connection this unique place gives us.

Coppermill Tower and Grabber Crane credit Penny Dixie

11 Reedbeds for life

We’ve planted almost two hectares of new Phragmites reedbeds, which you can see along the reservoir verges and around the islands.

As this habitat matures over the next decade it will attract even more wildlife. In summer look out for breeding reed warblers, reed buntings, moorhens and resting dragonflies. In winter the reeds may be sheltering an elusive water rail, snipe or, if you’re very lucky, even a bittern.

Stay a while and watch the reedbeds, you may see something special.

Fishermans way credit Penny Dixie

12 Cormorant Island

The islands on Reservoir 5 are easy to see thanks partly to the cormorants splashing it with a thick layer of white guano (also known as bird poo).

Cormorants began nesting at the Wetlands in 1991 and the colony grew rapidly to a peak of 360 nests in 2004. At least 159 nests were recorded in 2015, but they can be difficult to count. How many can you see today? As well as cormorants, Reservoir 5 is also of particular importance to wintering shoveler and gadwall. These ducks roost and forage in sheltered, undisturbed areas at the back of the reservoir, often intermingling with teal.

A pair of kingfishers can often be seen here too – they have a nest-hole on the island. Next door on Reservoir 4, tufted ducks gather in large flocks during late summer and early autumn. The ducks shed their flight feathers simultaneously, and are flightless until these have regrown.

The tufted ducks form closely-packed rafts in excess of 600-strong during this moult period, and are susceptible to disturbance. This is why access to these reservoirs is restricted so that we don’t disturb these special birds.

Cormorant at Walthamstow Wetlands credit Ian Phillips

13 Eye of the line

The Wetlands is London’s largest fishery – below the surface, these waters teem with fish. Each reservoir holds thousands of course and game fish, attracting anglers from across the country.

There are very distinct types of angling, each with strong identities and subcultures. And then there are the different species of fish for each type of angling – from carp and bream to trout and pike, each offer unique challenges for the dedicated angler.

Fisheries are not a recent feature in Walthamstow. Historical records tell us there were local fisheries here over a thousand years ago, before the Norman Conquest in 1066. The fine fishing on the River Lea is also celebrated in Izaak Walton’s book The Compleat Angler, first published in 1653.

Today, fisheries remain of integral importance to the heritage, management and ecology of the Wetlands

Fishing at Walthamstow Wetlands credit Penny Dixie

14 Precious Wetlands

Wetland habitats are rare in cities. Greater London has just 144 hectares of reedbeds, but this is increasing thanks to conservation efforts at sites such as Walthamstow and nearby Woodberry Wetlands.

Backflow silt from the reservoirs’ operations has provided ideal conditions for our new reedbeds to grow. Reeds absorb nutrients and pollutants, helping to improve water quality and increase biodiversity.

The cover they provide also offers better refuge areas for fish eggs and young (called fry). Amphibians and other small animals also benefit from this protection from predators. Establishing the reedbeds has also created new areas of shallow water. This will attract more wading birds and a host of other wildlife.

Walthamstow Wetlands Reservoir Reedbeds credit Penny Dixie

15 The Ferry Boat Inn

This Grade II Listed Building dates from around 1620 but there was probably a building here for centuries before that. It was built originally as a dwelling for the local ferryman, who transported people across the river.

For generations, the ferry was the sole means of crossing the Lea here until a bridge was built by Sir William Maynard in 1760. The building has also served as a farmhouse, posh country restaurant, tavern and even a morgue for unlucky people drowned in the Lea.

Unsurprisingly, it is rumoured to be haunted. The inn also has a long association with fishing. Over the years it’s surely been witness to plenty of anglers’ tales about ‘the one that got away’...

Ferry boat inn credit Walthamstow Wetlands credit Penny Dixie

16 The Two Towers

When Lockwood Reservoir was completed in 1903, the castellated tower behind you and its twin at the northern end of the Lockwood Reservoir was also built.

They house valves that control the flow of water pumped between the river and the reservoirs. If you look up at the wall of the outlet building here you’ll see an inscription: ELW. This was the insignia of the East London Waterworks Company, creators of the entire reservoirs complex between the 1860s and early 1900s.

Find out more about the story of the reservoirs when you visit the Engine House.

Lockwood southern tower Walthamstow Wetlands credit Penny Dixie

17 Who built Lockwood Reservoir?

It took a team of 1250 men! Lockwood was the last Walthamstow reservoir to be created, in 1903, and it is also the largest – covering around 30 hectares and excavated to a depth of around 8 metres.

Named after a director of the East London Waterworks Company, it was a major engineering feat for its day, requiring a huge labour force.

Unlike the first reservoirs, which were dug mainly by hand, Lockwood was constructed with plenty of steam-powered pumps, engines and cranes. As well as a team of 50 horses, 20 miles of railway track were also employed to assist in construction.

At around the same time, London’s population rose to six million. Demand for water was increasing constantly across the capital, prompting the need for even more reservoirs – this time further north in Chingford.

Lockwood reservoir Walthamstow Wetlands credit Penny Dixie

18 A quiet corner

Lockwood Reservoir is the highest bunded reservoir in the Wetlands complex, offering amazing views. Across the huge expanse of water you can see the London skyline in the distance and the Orbit sculpture in the Olympic Park.

This reservoir is also one of the best places for certain birds at the Wetlands because there is little disturbance. Look carefully for migrating waders such as dunlin, green and common sandpipers along the shoreline and winter ducks and grebes out on the open water.

The scrub at the northern end attracts small birds – and even the occasional rarity. A dusky warbler from Siberia was found here a few years ago, so keep your eyes and ears peeled!

Lockwood bund credit Penny Dixie

19 Lee Flood Relief Channel

Built in 1954 to prevent flooding, the channel usually holds less than a foot of still water – but at times of high rainfall, it becomes a fast-flowing torrent.

The channel runs from the top of the Lee Valley at Ware and down past the Chingford Reservoirs, where it joins the River Lee Diversion.

It splits again here at the eastern edge of the Wetlands by High Maynard Reservoir, flowing south past Reservoirs 4 and 5 and finally terminates at Stratford.

Lockwood reservoir credit Penny Dixie

20 High Maynard

Birds come and go at the Wetlands – every day is different.

During migration, waders may visit the shoreline here for just a few hours to feed and rest before moving on. Teal gather on the water in winter and great crested grebes and terns rear their young here in summer.

High Maynard may also support significant numbers of shoveler and gadwall in hard winter weather, as the flow of water through the reservoir results in some parts remaining ice-free.

During the spring and summer months Maynard’s islands have breeding pochard and tufted duck. These birds are potentially vulnerable to disturbance, and it is for this reason that public access to the eastern bank is restricted during this time.

High Maynard Lee Flood Relief Channel credit Penny Dixie